This year Finland and especially Lapland celebrates 70 years since the Lapland War ended and the museum Arktikum has put together a nice little exhibition about the Germans in Lapland between 1940-1944. The exhibition is on show at Arktikum until January 10, 2016.

From the day I came to Rovaniemi I have always heard about the Germans and their impact on Rovaniemi and Lapland because they almost completely burned Rovaniemi down when they left. I never found “the old Rovaniemi” as you usually find in every town. That is because there is no old Rovaniemi; the buildings are all built after 1945.

I little by little learned the history of how the Finns were forced to drive the Germans out of Finland by order from the Soviet Union. This was one of the conditions there would finally be peace between Finland and the Soviet Union after WWII. This started the Lapland War between Finland and Germany. I understood the Finns actually did not want to fight the Germans and the operation did take longer than Soviet Union had demanded, but Finland got the peace. But Lapland was to pay the price as the angry leaving Germans lit everything on fire. The Lapland War lasted between September 28, 1944 and April 27, 1945.

There were some 220 000 Germans in Lapland, about 6 000 of them in Rovaniemi area between 1940 and 1944. That is almost as many as the local population of Lapland in those days. (Today we say there are 200 000 people and 200 000 reindeer in Lapland). The amount of Germans were divided into 4 000 officers, 22 000 non-commissioned officers, 113 000 army soldiers, 21 000 SS soldiers and 30 000 air force soldiers.

As I visited the exhibition I finally got the answer why the Germans were here in the first place, which my history lessons at school had forgotten to mention….

In September 1940, Finland and Sweden signed transit agreements with Germany permitting troops and material required by the Germans occupying Northern

Norway to pass through their territory. As a result, the railways and roads of the north were filled with German troops and munitions in growing numbers. A wide range of active contacts that last for several years evolved in the region between the Finns and the Germans.

The second Wold War (WWII) was going on in Europe. Finnish-German military cooperation made North Finland a war zone for Germany troops from 1941 to 1944, but Finnish Lapland was not occupied by the Germans.

Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Three days later, Finnish towns were bombed by Soviet aircraft, and Finland now considered itself to be in the Continuation War against Soviet Union, fighting alongside Germany. The headquarters of the Finnish Army, under Commander-in-Chief Mannerheim gave the war zone of North Finland over to the Germans, with the Sixth Division of the Finnish Army under German command. There were two German army corps in Finnish territory; one in Petsamo and the other in the Salla region. Their supreme command was originally in Oslo in Norway, but the headquarters of the 20th Gebirgsarmee founded in January 1942, was located in Rovaniemi. The army’s task was to defend North Finland, attack Murmansk and cut off the railway leading south from Murmansk.

The Finns in Lapland considered the Germans to be handsome, had good bearing and sang cheerfully. In Rovaniemi the soldiers were enthusiastic to look after their appearance and one reason for that, was that barbers in Finland were women, unlike back home in Germany, where the barbers were only men.

By the autumn of 1941, there were over 630 German accommodation- and storehouse barracks in the Rovaniemi area. The various services of German information and cultural institutions such as theater, bookstore, artists’ residence and radio station in Rovaniemi were also enjoyed by local residents. In particular, the cultural facility know as “Haus der Kameradschaft”, completed in 1943, was an impressive building with 350 seats and a large stage. Finnish and German entertainers performed there, and the most popular events were screenings of films and concerts. The Germans would often give free tickets to their Finnish neighbors and friends.

The Germans in Lapland provided work for the Finns, too. Approximately 12 000 Finns were employed in the Province of Lapland by the Germans by February 1944. It also turned out that the Germans paid considerably higher wages than Finnish employers and many workers moved from one work site to another in search of better pay. Women were offered employment working as nurses, clerical staff, washerwoman, cleaners and casual laborers. Young people also had an opportunity to earn good wages at German work sites.

The Germans had a lot of professional skills that were not to be found in the outlying regions of Lapland. There were doctors, dentists or veterinarians among the Germans. I have read the interesting book in Finnish written by doctor Emil Conzelmann about his work in Rovaniemi during these years (Tohtori Conzelmannin sotavuodet Lapissa). The Germans also carried out a great deal of electrical and repair work for local people. (Which however they destroyed as they left Rovaniemi.)

Any Finn with the slightest knowledge of German was asked to be an interpreter.

The arrival of the German troops marked the beginning of a boom period for retailers in Lapland. Shops in Finland offered goods that were not easily found in Germany in those days, such as radio receivers, fur coats, women’s underwear and wristwatches. You can easily understand there was a boom in business as the amount of inhabitants grew by 100%. The Germans had Finnish money and they bought a lot of things.

Finnish women and German soldiers could come into contact with each other in many different situations. German soldiers on leave held small soireés and parties in their barracks. During the war, these were of course a welcome change and entertainment for everyone. According to newspapers, some thirty Finnish-German weddings took place between 1940 and 1944. According to estimates, some 250 Finnish women followed their German loved ones to their new country in the last stages of the war and afterwards. A sad story is about the woman, who had to return back to Finland again, after she was not found suitable to marry a German. She did not have the Arian look, that was considered ideal at that time in Germany.

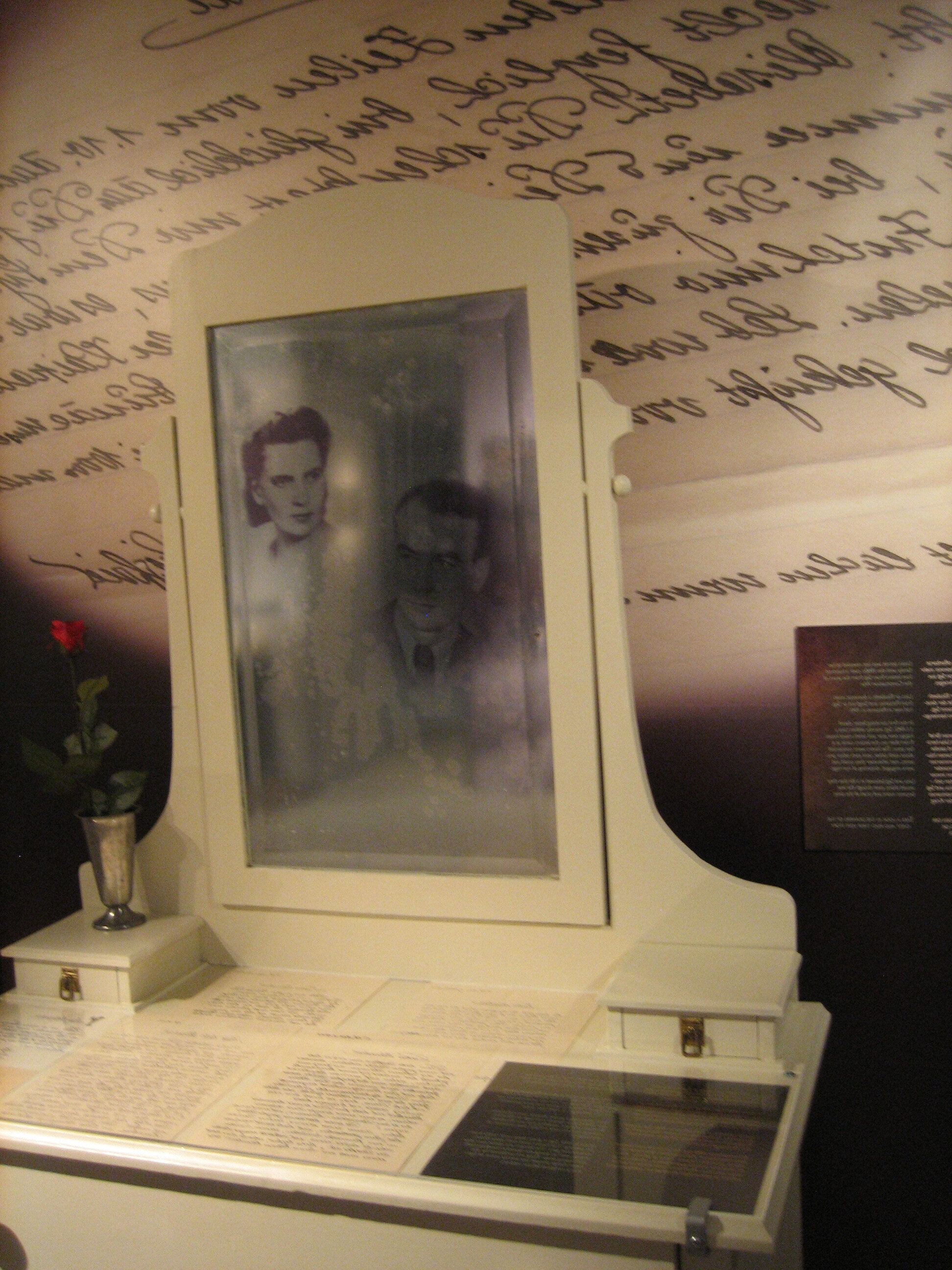

The exhibition tells about love stories between German men and Finnish women. You can spend a long time there reading love letters. In a chest there is something connected to the German period in every drawer for you to find out. There is also a desk with interesting documents and newspapers from the period.

It is estimated that there are less than a thousand people in Finland who were born out-of-wedlock to Germans. Between 1943 and 1945, 264 children were born out of marriage in the township of Rovaniemi The children of Germans were a banned subject of conversation for many years, and even the mothers did not want to tell their children of what had happened.

The Germans were friendly to children in Rovaniemi and could often give them sweets, chocolate and bread. As the soldiers had to spend a long time in a foreign country away from home they missed their families and children. The Germans also held Christmas parties and gave Christmas presents for young Finnish children. In smaller villages all the children and their mothers were invited, while in larger communities only poor families were invited.

Finns showed their hospitality by inviting Germans to the sauna, and it was impolite to turn down such an invitation. The Germans gradually learned that the sauna was not a health risk and they began to enjoy it. For Germans, the first time in the sauna was often a memorable event. They even started to call themselves “Saunisten”.

There are many stories about Generaloberst Dietl, the commander of the 20th Mountain Army during the invasion of Norway. He was regarded as pleasant and also described as a friend of Finland with a sense of humor. He required his troops to be friendly to Finns and also set a good example in this respect.

After 1945 bitterness among the Finns against the former “comrades-in-arms” that was caused by the Lapland War led to decades of suspicion of all German things. Returning soldiers, who came to visit their brides and children left in Finland, were victims of repeated vandalism and German tourists would hear catcalls.

In Norvajärvi in Rovaniemi German organizations financed the building of a mausoleum in 1963 at the cemetery for the German war dead. On the opening day of the cemetery, local communists staged a demonstration with over 300 participants. Public opinion, however, seemed to take the view that the last resting place of the dead must be respected: “You can’t hate dead bodies”.

If you visit this exhibition you will also learn there is an app you can get from AppStore or GooglePlay called “Kuvat eläväksi”. If you download that (it is for free; found under “Lapin maakuntamuseo”) to your iPad or IPhone you can, by pointing the camera function on the device towards the pictures marked with a red ring, get the picture alive and the person on the picture starts to tell you a story based on memories and stories from that time. Unfortunately only in Finnish for now. But it was quite surprising to see the people in the picture start moving. There are three such pictures in the exhibition. Ask the staff for help, if you do not get it to work.