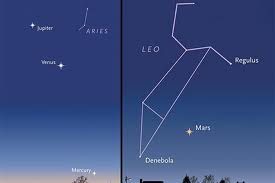

During the winter nights in Lapland there is one star shining brighter than the others. The Venus star is the second planet from the Sun; Mercury is nearer to the Sun. It is named after the Roman goddess of love and beauty. After the Moon it is the brightest natural object in the night sky. In Lapland you can see it during the clear nights in the west after the sunset. It is often called the “evening star”. Venus is always brighter than any star (apart from the Sun). The planet is bright enough to be seen in a mid-day clear sky, and it can easily be seen when the Sun is low on the horizon. Venus, like the other planets, has no shine of itself. The Sun provides the shine.

This photo I have taken after sun set in the west. It was a clear night with millions of stars, but one was shining brighter than the others…

Venus is a terrestrial planet and is sometimes called Earth’s “sister planet” because of their similar size, mass, proximity to the Sun and bulk composition. The atmospheric pressure at the planet’s surface is 92 times that of Earth’s. With a mean surface temperature of 735 K (462 °C; 863 °F), Venus is by far the hottest planet in the Solar System, even though Mercury is closer to the Sun. Venus’ surface is a dry desertscape interspersed with slab-like rocks and periodically refreshed by volcanism.

Venus “overtakes” Earth every 584 days as it orbits the Sun. As it does so, it changes from the “Evening Star”, visible after sunset in the west, to the “Morning Star”, visible before sunrise in the east. Venus is hard to miss when it is at its brightest. Its greater maximum elongation means it is visible in dark skies long after sunset. As the brightest point-like object in the sky, Venus is a commonly misreported “unidentified flying object”. U.S. President Jimmy Carter reported having seen a UFO in 1969, which later analysis suggested was probably Venus. Countless other people have mistaken Venus for something more exotic.

There has been a great interest in exploring Venus from both the Soviet Union’s and the United States’ side and they have launched several robots to go to Venus. Some have crashed already on their way and some have crashed on the surface of Venus. But due to the big amount of robots sent to Venus there has been results about temperature and surface construction. All results have proven that on Venus there could not be any life, like on Earth, because of the enormous heat on the surface.

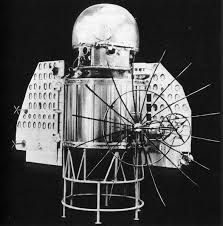

Here is a description of some of the first robots sent to Venus. The program has continued still in 1990:ies.

The first robotic space probe mission to Venus, and the first to any planet, began on 12 February 1961, with the launch of the Soviet Union’s Venera 1 probe. The first craft of the otherwise highly successful Soviet Venera program, Venera 1 was launched on a direct impact trajectory, but contact was lost seven days into the mission, when the probe was about 2 million km from Earth. It was estimated to have passed within 100,000 km of Venus in mid-May.

The United States exploration of Venus also started badly with the loss of the Mariner 1 probe on launch. The subsequent Mariner 2 mission, after a 109-day transfer orbit on 14 December 1962, became the world’s first successful interplanetary mission, passing 34,833 km above the surface of Venus. Its microwave and infrared radiometers revealed that although the Venusian cloud tops were cool, the surface was extremely hot—at least 425 °C, confirming earlier Earth-based measurements and finally ending any hopes that the planet might harbor ground-based life.

The Soviet Venera 3 probe crash-landed on Venus on 1 March 1966. It was the first man-made object to enter the atmosphere and strike the surface of another planet. Its communication system failed before it was able to return any planetary data. On 18 October 1967, Venera 4 successfully entered the atmosphere and deployed science experiments. Venera 4 showed the surface temperature was even hotter than Mariner 2 had measured, at almost 500 °C, and the atmosphere was 90 to 95% carbon dioxide.

One day later on 19 October 1967, Mariner 5 conducted a fly-by at a distance of less than 4000 km above the cloud tops.

Armed with the lessons and data learned from Venera 4, the Soviet Union launched the twin probes Venera 5 and Venera 6 five days apart in January 1969; they encountered Venus a day apart on 16 and 17 May. The probes were strengthened to improve their crush depth to 25 bar and were equipped with smaller parachutes to achieve a faster descent. Because then-current atmospheric models of Venus suggested a surface pressure of between 75 and 100 bar, neither was expected to survive to the surface. After returning atmospheric data for a little over 50 minutes, they were both crushed at altitudes of about 20 km before going on to strike the surface on the night side of Venus.